Every moment of a science fiction story must represent the triumph of writing over worldbuilding.

Worldbuilding is dull. Worldbuilding literalises the urge to invent. Worldbuilding gives an unnecessary permission for acts of writing (indeed, for acts of reading). Worldbuilding numbs the reader’s ability to fulfill their part of the bargain, because it believes that it has to do everything around here if anything is going to get done.

Above all, worldbuilding is not technically neccessary. It is the great clomping foot of nerdism. It is the attempt to exhaustively survey a place that isn’t there. A good writer would never try to do that, even with a place that is there. It isn’t possible, & if it was the results wouldn’t be readable: they would constitute not a book but the biggest library ever built, a hallowed place of dedication & lifelong study. This gives us a clue to the psychological type of the worldbuilder & the worldbuilder’s victim, & makes us very afraid. (—M. John Harrison)

It was the quote heard ’round the nerddom; it set the blogosphere aflame and rose the hackles of readers reared on the likes of J.R.R. Tolkien, Robert Jordan, and Stephen Donaldson. He’s an “utter, arrogant asshole” they yelled. Or, “he probably realised he could never come close to Tolkien in worldbuilding and decided it was just unnecessary crap.” Whether in agreement or disagreement with Harrison, shouts were raised and battlelines drawn, all in the name of worldbuilding and its importance to the genre.

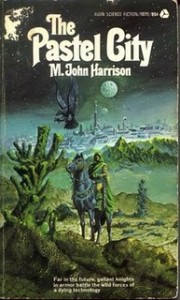

And, okay, I’ll admit it, I was one of those angry trolls, though not so nasty in my criticism. I turned up my nose at Harrison, shrugged off his fiction because of (what I considered) off-base commentary on his blog. So, then, it was with obvious, pride-compromising trepidation that I accepted a challenge from Sam Sykes, author of Tome of the Undergates, to tackle Harrison’s work. Along with several others, I was tasked with putting aside my preconceptions, and broadening my horizons by reading a novel that was outside my wheelhouse. Sykes’s choice for me was The Pastel City, the first of Harrison’s many stories set in and around the city (or cities?) of Viriconium.

Some seventeen notable empires rose in the Middle Period of Earth. These were the Afternoon Cultures. All but one are unimportant to this narrative, and there is little need to speak of them save to say that none of them lasted for less than a millennium, none for more than ten; that each extracted such secrets and obtained such comforts as its nature (and the nature of the universe) enabled it to find; and that each fell back from the universe in confusion, dwindled, and died.

The last of them left its name written in the stars, but no one who came later could read it. More important, perhaps, it built enduringly despite its failing strength—leaving certain technologies that, for good or ill, retained their properties of operation for well over a thousand years. And more important still, it was the last of the Afternoon cultures, and was followed by Evening, and by Viriconium. (p. 5)

And so opens The Pastel City, with a three-and-a-half page long infodump. Wait. But I thought Harrison hates worldbuilding? Well, yeah, he kind of does. But that’s also kind of the point. It’s like he’s flipping the bird to all those readers who expect to be hand-fed the setting. Ultimately, this section goes a long way in establishing the story to follow and is, besides a few instances here and there throughout the novel, the only background information you’re given about the world of the The Pastel City.

Harrison’s universe has a deep history, spanning millennium long civilizations, but, unlike contemporary authors like Brandon Sanderson or Joe Abercrombie or Steven Erikson, he skirts around that history, only feeding the reader the essential information necessary for them to grasp the situation in the novel. In many ways, it’s easy to be reminded of cinema, a storytelling medium that has little room for extraneous exposition and must focus on the here-and-now of the story. Harrison teases the reader with past events and hints at a wider world, but quickly moves past these distractions, letting the reader fill in the gaps as they will (or not at all, for the author deemed those gaps unnecessary to the overarching plot). Do we as readers need to know why the marshes are poisoned by liquid metal? Or simply that they pose a threat to our protagonists? In many ways, it hearkens back to the simple storytelling found in classic Swords & Sorcery, a sub-genre well revered for its no-fat-on-the-bone storytelling.

From what I gather, Harrison’s other Viriconium stories are less straight-forward than The Pastel City, and perhaps that is where Harrison’s experimental opinions and philosophies are in clearer evidence; but, to my surprise, The Pastel City presents a fairly straightforward plot. It’s typical quest-style fantasy: a besieged city, two warring queens, northern barbarians and a motley band of heroes. Consider, though, that The Pastel City was written in 1970, a full seven years before Terry Brooks and Stephen Donaldson re-invigorated the genre, and it’s alarming to see how readily The Pastel City resembles the work of some of today’s most prominent fantasy authors.

As a young(ish) reader, one thing I must constantly challenge myself to do is go back and explore the roots of the genre beyond my initial readings as a boy. There’s always that pressure, as a blogger and reviewer, to keep up with the times and be on the cutting edge of new releases, and I wasn’t yet a glimmer in my momma’s eye when The Pastel City was released in 1970; yet so much of Harrison’s work is recognizable in those aforementioned new releases and their young authors—Ken Scholes’ Psalms of Isaak tells the tale of a besieged and shattered city, a wasteland full of ancient relics and mechanical men; Mark Charan Newton’s Legends of the Red Sun features “magic” that is little more than the misunderstood relics of an ancient civilization. Airships, metallic animals and towering suits of mechanical power armour even hint at steampunk, a sub-genre that’s hotter than everything but vampires. And the way Harrison mixes adventurous fantasy with science fiction shares similarities with another 1977 tale called Star Wars: A New Hope. You may have heard of it. It changed the landscape for science iction storytelling in all mediums.

This isn’t to assume that Harrison directly influenced these writers and storytellers (though Newton’s gone on record with his admiration for Harrison’s Viriconium tales), but he was certainly ahead of his time and so The Pastel City holds up to scrutinization as well now as it did when it was first released 40 years ago.

The Pastel City was written before faux Medieval Europe took its place atop the heap of go-to settings for fantasy writers and, like Star Wars, The Pastel City never lets up in throwing new, breathtaking locales at the reader. The structure of the story is familiar and the land through which tegeus-Cromis travels through is eerie and depressing, but never resorts to the doom, gloom, brown, and grey of so many other post-apocalyptic novels. Where Brooks and Newton write about a post-apocalyptic world covered by the veneer of a recognizable fantasy world, Harrison uses it as an excuse to create something wholly unique and alien.

In the water-thickets, the path wound tortuously between umber iron-bogs, albescent quicksands of aluminum and magnesium oxides, and sumps of cuprous blue or permanganate mauve fed by slow, gelid streams and fringed by silver reeds and tall black grasses. The twisted, smooth-barked boles of the trees were yellow-ochre and burnt orange; through their tightly woven foliage filtered a gloomy, tinted light. At their roots grew great clumps of multifaceted translucent crystal like alien fungi.

Charcoal grey frogs with viridescent eyes croaked as the column floundered between the pools. Beneath the greasy surface of the water unidentifiable reptiles moved slowly and sinuously. Dragonflies whose webby wings spanned a foot or more hummed and hovered between the sedges: their long, wicked bodies glittered bold green and ultramarine; they took their prey on the wing, pouncing with an audible snap of jaws on whining, ephemeral mosquitoes and fluttering moths of april blue and chevrolet cerise.

Over everything hung the heavy, oppressive stench of rotting metal. After an hour, Cromis’ mouth was coated with a bitter deposit, and he tasted acids. He found it difficult to speak. While his horse stumbled and slithered beneath him, he gazed about in wonder, and poetry moved in his skull, swift as the jewelled mosquito-hawks over a dark slow current of ancient decay. (pp. 47-48)

Harrison’s prose is wonderfully evocative. He paints a vibrant, eerie picture of a post-apocalyptic landscape, and fills the land with skeletal cities and the long-rotted remnants of a lost civilization; poisonous swamps, where even the clearest water will serve you a painful death; giant dragonflies, a Queen’s shambling sloth-like beasts and the hulking, lightsaber-wielding chemosit. Harrison’s world is Middle-Earth gone to shit, but no less beautiful and visually arresting for its demise. Its history and lore might not be so deeply realised, but Harrison’s world exists with no less power and resonance in the mind of the reader than Tolkien’s seminal Middle-Earth.

What startled me further, especially given the publication date of the novel, was Harrison’s small foray into the philosophies of cloning and, ultimately, what we now look to with stem cell research.

During a period of severe internal strife toward the end of the Middle Period, the last of the Afternoon Cultures developed a technique whereby a soldier, however hurt or physically damaged his corpse be, could be resurrected—as long as his brain remained intact.

Immersed in a tank of nutrient, his cortex could be used as a seed from which to “grow” a new body. How this was done, I have no idea. It seems monstrous to me. (p. 105)

It’s not a fully-featured exploration of the idea (like everything in the novel, it’s sniffed at by Harrison, fed to the reader just enough that they get curious, and then taken away), but it is another example of Harrison’s prescience and shows that he had a pretty firm idea of how not only the genre was going to evolve, but also how our sciences and culture might also grow.

Ultimately, I believe the purpose of Sykes’ challenge to bloggers was to expand their understanding of the genre. Happily, my experience with The Pastel City has done just that. I was ready to hate on it; ready to throw my prejudices at Harrison and his work, but from the early pages, I realized the error in my thinking. The Pastel City is a shining example of the roots of both fantasy and science fiction and deserves its place along the classics it has obviously inspired.

Harrison might not be so widely read as Terry Brooks or Stephen Donaldson, but his influence on the genre is undeniable. You’d be hard-pressed to read recent fantasy and not see the echoes of The Pastel City, whether the author’s been directly influenced by Harrison or not. Like anything that steps beyond the comfortable boundaries expected of it, Harrison’s work has its share of detractors, but for all those complaints about his future work, The Pastel City is an easily-accessible, forward thinking fantasy adventure.

Tolkien famously wrote a “All that is gold does not glitter” and The Pastel City is proof of this. Harrison’s reputation precedes him, but those adventurous enough to look beyond that will find a fun, dangerously astute ode to old school science fiction and fantasy.

Aidan Moher is the editor of A Dribble of Ink, a humble little blog that exists in some dusty corner of the web. He hasn’t won any awards, or published any novels. But he’s, uhh… working on that.

He is also a contributor at SF Signal and the lackey for io9’s Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy podcast.